|

NITRO

HALLUCINATION

Hope you enjoy this ride into the past; the edited version of this article ran in HOT ROD magazine in the January 2001 issue. Based on response, we'll try to have more material up here soon…

|

HEY STUNKARD! - Can I get a copy of that fire burnout photo?

YES,

CLICK HERE! |

Barnstorming Rural Arkansas

in a Vintage S/FX Dodge

Story and photos by Geoff Stunkard

Virtually anybody who has been driving cars, especially hot rods, knows that sinking feeling. The flashing light rack on the top of the police

car was closing in fast, and from the pit of your stomach, all you can do is hope against hope it isn't for you. The mighty Mississippi River and the Missouri border were less then five miles away, but a second-long wail from the siren as the car pulled up behind me meant that I'd indeed be a little later than I had planned. After pulling off to the side of the interstate, I put the rental car into park and watched nervously in the rear view mirror as a big Tennessee State trooper adjusted his hat, picked up his ticket book, and walked up to the car. Virtually anybody who has been driving cars, especially hot rods, knows that sinking feeling. The flashing light rack on the top of the police

car was closing in fast, and from the pit of your stomach, all you can do is hope against hope it isn't for you. The mighty Mississippi River and the Missouri border were less then five miles away, but a second-long wail from the siren as the car pulled up behind me meant that I'd indeed be a little later than I had planned. After pulling off to the side of the interstate, I put the rental car into park and watched nervously in the rear view mirror as a big Tennessee State trooper adjusted his hat, picked up his ticket book, and walked up to the car.

“Good afternoon, officer. Is there a problem?”

“Other than clocking you at 80 MPH, no....”

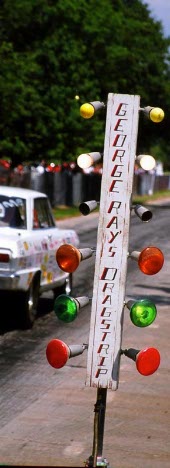

It was soon after the 12th Annual Goodguys race at Indy in June that I had contacted HOT ROD editor Ro McGonegal about the possibilities of going to Arkansas to report on what is arguably the “purest” drag strip left in America. Located in the town of Paragould, George Ray's Wild Cat Hot Rod Drag Strip is a virtual historic landmark operating on 3000 feet of vintage concrete in the backyard of one Mr. George Ray. Unsanctioned and obscure, the icing on the cake was the fact that nostalgia racer Brian Kohlmann was bringing his 1965 altered-wheelbase Dodge Coronet in from Racine, Wisconsin for a one-time appearance. This near-identical replica of the Mr. Norm / Gary Dyer machine is not only powered by a blown Hemi, but running on a solid dose of nitro, something most of the resident attendees at George Ray's had not experienced in a long time.

This combination of factors held ideal opportunities to truly turn back the clock. After all, it was here in the expanses of the Mississippi River bottoms that some great early drag racing had occurred. Down near Memphis, the now-defunct Lakeland Drag Strip had been the site of one of the first-ever blown funny car events, with guys like Arnie Beswick, Don Gay, Bob Sullivan, and others booked in for an 8-car “Supercharged King of Kings” barnburner as early as 1966. Moving upstream in the direction of Chicago was Alton, Ill., where Chris “The Greek” Karamesines had clocked the first (and very controversial) 200 MPH run and where Doug “Cookie” Cook was almost killed one night in 1967 in the ever-impressive Stone-Woods-Cook Mustang funny car. From Cordova, Ill. to

La Place, La., the mother river had birthed both big and little drag strips, many of which are gone now. With Kohlmann's Dodge as a specimen, the idea was to put the vintage car in the vintage environment, do some rosin and fire burnouts, gauge the crowd's reaction and recreate a weekend of era-specific exhibition racing.

Right now, however, the impending ticket was the most looming issue. After the transmission in my own car had taken a complete dump eight hours earlier, I had been able to get a rental car and continue the journey (assisted in great measure by Knoxville Mopar mavens Ken and Matt Hensley), but had been pushing the Pontiac Grand Am hard to make a Saturday night date at another unsanctioned track in Sikeston, Mo., where I would hook up with Kohlmann and his crew. With a smile, the officer handed back my driver license and paperwork and I was on my way...

Seventy miles north of the riverside Arkansas-Missouri border is a Saturday night hotspot named Sikeston Drag Strip, located right on I-55. By the time I pulled through the pit gate at 6:30 PM, light drizzle was falling, but Kohlmann and his three-man crew (Keith Christianson, and Pete and John Ores) had already unloaded the car and were working on it underneath a collapsible canopy. Charles Jolliff, a local fan who helped coordinate the trip, shook my hand and said with a southern drawl that the rain wasn't expected and would be over soon. He was right. By 8:00, things had dried enough to start the evening's 100-car bracket race. Track owner Ray Poirier had declined to book the car in ahead of time since he did not have a chance to advertise it, but had graciously let the team in for free. And, racers being racers, it was decided that the Dodge, which had drawn quite a pitside crowd early in the night, would go out and make a mild run to prepare for the trip to Paragould in the morning.

Much had been written over the years about the mystery of nitromethane as a fuel. Regardless of who used it first and what type of machinery it was used in, today the chemical compound using the symbol CH3NO2 has become the mainstay of drag racing, and the fuel's signature smell and

horsepower-generating capacity is a primary attraction for many adherents. Its extremely destructive nature when utilized in larger quantities is documented as well. Cautiously, Kohlmann has crept up on the combination in the Dodge, which presently runs someplace between 40 to 45 percent in the eight-gallon Moon tank located behind the grille. Much had been written over the years about the mystery of nitromethane as a fuel. Regardless of who used it first and what type of machinery it was used in, today the chemical compound using the symbol CH3NO2 has become the mainstay of drag racing, and the fuel's signature smell and

horsepower-generating capacity is a primary attraction for many adherents. Its extremely destructive nature when utilized in larger quantities is documented as well. Cautiously, Kohlmann has crept up on the combination in the Dodge, which presently runs someplace between 40 to 45 percent in the eight-gallon Moon tank located behind the grille.

At 34, Brian Kohlmann may not be considered a likely candidate for this type of project. A cardiovascular technician by trade, he discovered the altered-wheelbase era through the musty pages of old magazines less than a decade ago. A long-time Mopar fan, he was already bracket racing an injected 1964 Plymouth at the time. Through his research, he found that the years 1965 and 1966 had marked the end of A/FX as the top class in stock-bodied drag racing. More radical creations, built for match racing more than sanctioned competition, took the racing nation by storm, producing a hybrid between a Super Stock machine and a fuel altered that gave birth to the moniker “funny car.” Smitten, Kohlmann decided to replicate the one Dodge that had been considered the most radical of that period – Mr. Norm's Supercharger.

In the mid-Sixties, Norm Krause's Grand-Spaulding Dodge dealership in Chicago was on the cutting edge of performance car sales, and “Mr. Norm” spearheaded a racing program with a young mechanic under his tutelage named Gary Dyer. Not wanting to beat his own customers, Krause financed the construction of a series of supercharged stockers for exhibition racing and promotions. The most radical version in the pre-fliptop, or “flopper,” funny car era was built from a car the team had bought from Dick Branster in mid-1965, Roger Lindamood's “Color Me Gone” altered-wheelbase Coronet. One of only 11 such cars that Chrysler itself had created for that season, this acid-dipped, reworked Dodge would shock the fans in October of ‘65 when Dyer drove it to an unheralded 8.63 in a well-remembered race with arch Pontiac rival Don Gay at Lions Drag Strip. By the time a fiberglass Charger replaced it in mid 1966, the car had dipped down into the 8.40s before it disappeared into the eons of time. Undaunted, Kohlmann started with a clean slate to create the tribute replica.

The “new” car had also begun life as a 1965 Dodge Coronet 500 hardtop, one that a previous race owner had already acid-dipped and made a wheelbase change to. Bought as a roller, Kohlmann added a combination of early speed parts and late model engine and safety technology to make it look, feel, and function like Dyer's ride, yet is still maintainable. Take the driveline, for instance. In the engine bay is an easily-replaced Keith Black block with current-era nitro parts (Crane supplied a special cam) and Brad Anderson heads, topped off with the vintage 6-71 blower and Hilborn Model E injector hat. Unlike the Torqueflites used in the original, the car has a Bruno converter adapter unit and heavy duty Dynamic converter mounted in front of a three-speed Lenco, and a 1965 vintage Dana 60 holds a set of rare 3.70 ratio Top Fuel gears. The “new” car had also begun life as a 1965 Dodge Coronet 500 hardtop, one that a previous race owner had already acid-dipped and made a wheelbase change to. Bought as a roller, Kohlmann added a combination of early speed parts and late model engine and safety technology to make it look, feel, and function like Dyer's ride, yet is still maintainable. Take the driveline, for instance. In the engine bay is an easily-replaced Keith Black block with current-era nitro parts (Crane supplied a special cam) and Brad Anderson heads, topped off with the vintage 6-71 blower and Hilborn Model E injector hat. Unlike the Torqueflites used in the original, the car has a Bruno converter adapter unit and heavy duty Dynamic converter mounted in front of a three-speed Lenco, and a 1965 vintage Dana 60 holds a set of rare 3.70 ratio Top Fuel gears.

With technical help from Norm Krause himself, a sprung, chromed straight front axle and 1963 Corvair steering box replaced the stock front suspension parts. While the car sports an up-to-date funny car style cage, it still uses the original frame and a good percentage of the factory steel body. A four-link outfit replaced the rear springs only because the fuel motor wound them up so hard that it tore up the transmission mounts. Kohlmann even went so far as to pay Deist Safety a hefty premium to create an SFI-certified “silverized” fire suit to go with a vintage charcoal breather and maskless helmet.

Endeavors like this cost money, real money, and through the help of sponsors like Belle Dodge, Racine Harley-Davidson, Cost Cutters Family Hair Care, Radir Wheels and Lucas Oil Products, Kohlmann has been able to create the past in strikingly exact form. Mr. Norm graciously gave permission to paint the signature Grand-Spaulding “ram” on the doors, and the S/FX (Supercharged/Factory Experimental) Mopar now captures the flavor of the era to a ‘t'.

A crowd has gathered around the base of the Sikeston tower as the Dodge fires up. The smell of nitro fills the night air, and Kohlmann smokes the tires halfway down the eighth mile track on the burnout. Trying to make traction, however, the second dry hop off the starting line results in problems, as the torque of the motor and now-biting Goodyears literally rip the steel flywheel support completely off the back of the well-engineered converter. Pushed back to the pits, everybody starts getting dirty as hot pieces come apart. Brian walks the pits to find another converter.

As built, the combination in the Dodge has been reliable, and this is the first catastrophic failure in 50 passes, and the first-ever for a converter since Brian switched to Dynamic Products (which is why the team itself does not have a spare on hand). Since the George Ray track is the main reason for being here, the car has to be fixed tonight. A local bracket pilot named Junior Ferrel lends Kohlmann a spare converter, albeit one with a stall speed way above the 2200 RPM lock-up on the original unit. But beggars can't be choosers. Two and a half hours later, as Sunday morning begins on the clock, the replacement is in the housing, everything is bolted up and the sound of the supercharged fuel motor being fired is heard only by the few remaining racers on the property. Ray Poirier comes over and gives Brian a $100 bill out of graciousness, and by 1:30 we are loaded up and on our way toward the Arkansas border.

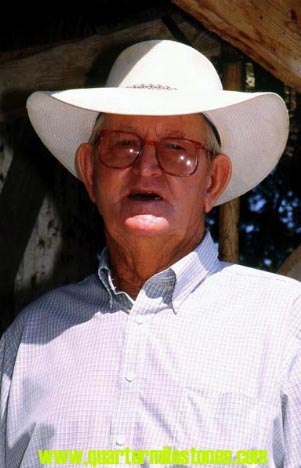

“He's the closest thing to John Wayne you'll ever meet, a true legend,” was Chucky Jolliff's comment on George Ray. A hardscrabble-type cotton picker and logger early in life, by the late 1950's George Ray was running a successful little garage in Paragould and building hot rods. At the time, the closest drag strip was located in Halls, Tenn., across the Mississippi and accessible primarily by ferryboat. Memphis locals like Ray Godman, Bill Taylor, Joe Lunati and Larry Coleman were regulars, and one afternoon, George proceeded to tell the track promoter that he and other members of the Arkansas gang weren't getting a fair shake. He was told by the local police later that day that he wasn't wanted as a racer in the Volunteer State any longer, Ray decided ‘to hell with ‘em, I build my own drag strip.' By 1961, the purchase of a narrow 10-acre farm just outside the town itself made that statement a reality. “He's the closest thing to John Wayne you'll ever meet, a true legend,” was Chucky Jolliff's comment on George Ray. A hardscrabble-type cotton picker and logger early in life, by the late 1950's George Ray was running a successful little garage in Paragould and building hot rods. At the time, the closest drag strip was located in Halls, Tenn., across the Mississippi and accessible primarily by ferryboat. Memphis locals like Ray Godman, Bill Taylor, Joe Lunati and Larry Coleman were regulars, and one afternoon, George proceeded to tell the track promoter that he and other members of the Arkansas gang weren't getting a fair shake. He was told by the local police later that day that he wasn't wanted as a racer in the Volunteer State any longer, Ray decided ‘to hell with ‘em, I build my own drag strip.' By 1961, the purchase of a narrow 10-acre farm just outside the town itself made that statement a reality.

Onto the former soybean fields went a strip of concrete 2960 feet long (which allowed for quarter-mile races and a safe down area for the cars of the era), and, by November of 1961, George Ray's Wild Cat Hot Rod Drag Strip was in business. Despite efforts by both county and city politicians to stop the track's construction and operation at the time, George prevailed. For next thirty-nine years, the track has opened on the first weekend in March, weather permitting, and given the locals a place to spend a Sunday afternoon until the cold days of late October. Onto the former soybean fields went a strip of concrete 2960 feet long (which allowed for quarter-mile races and a safe down area for the cars of the era), and, by November of 1961, George Ray's Wild Cat Hot Rod Drag Strip was in business. Despite efforts by both county and city politicians to stop the track's construction and operation at the time, George prevailed. For next thirty-nine years, the track has opened on the first weekend in March, weather permitting, and given the locals a place to spend a Sunday afternoon until the cold days of late October.

“It's not as crazy as it used to be,” says Darryl Dickson, a former starter who has been coming to George's since the early 1960s. “People are a little more mature now...“

Such was not the case in earlier times, when George walked around with a loaded pistol in his belt to deal with troublemakers and potential bandits (he still keeps the gun with him, even today). Back then, fights between drunks were a common problem, and George himself was the long arm of the law in sending

them on their way home. One night, a particularly obnoxious racer busted out all the windows in the ticket booth near George's house on his way out, and George and Darryl chased him all the way to the Missouri state line.

As for George himself, well, John Wayne would have been hard-pressed to equal him. For instance, one afternoon, while George was working on the starting line, an errant racecar hit him, severely breaking his arm. He flagged cars off the rest of the day with his good arm before going to the hospital. The plaster cast was on for about two days before George got tired of it being in the way and cut it off with a hacksaw. Or the time he showed up at a neighbor's house one afternoon holding his privates, which had been damaged in a farm accident. Deciding he didn't need that doctor all the way over in Jonesboro after all, George reinserted the loose testicle and sewed himself back up. Nope, they don't make guys like George Ray any longer....

To find George Ray's Wild Cat Hot Rod Drag Strip, one gets on Route 412 from I-55 in Hayti, Mo., and drives east. Paragould, Ark. is located just over the state line, off the little tip of Missouri that sticks out like a big toe in the “Show Me” state's southeast corner. Make a left onto Route 135 South just before you get into the town itself, and go about a mile down, looking for a farmhouse on the left with a neat row of flowers planted along the front edge of the yard. At the end of the flower bed, on a post, is an old grocery store sign repainted to read “George Ray's Drag Strip.” It, in turn, is at the edge of a gravel road, which leads to the ticket booth where you pay $6.00 per person to get in. Jolliff met us in Kennett, Mo., where Kohlmann and our band of match race gypsies had spent the short night, and led us out to the track Sunday morning. “Enter At Your Own Risk” signs are prominently displayed. To find George Ray's Wild Cat Hot Rod Drag Strip, one gets on Route 412 from I-55 in Hayti, Mo., and drives east. Paragould, Ark. is located just over the state line, off the little tip of Missouri that sticks out like a big toe in the “Show Me” state's southeast corner. Make a left onto Route 135 South just before you get into the town itself, and go about a mile down, looking for a farmhouse on the left with a neat row of flowers planted along the front edge of the yard. At the end of the flower bed, on a post, is an old grocery store sign repainted to read “George Ray's Drag Strip.” It, in turn, is at the edge of a gravel road, which leads to the ticket booth where you pay $6.00 per person to get in. Jolliff met us in Kennett, Mo., where Kohlmann and our band of match race gypsies had spent the short night, and led us out to the track Sunday morning. “Enter At Your Own Risk” signs are prominently displayed.

With the track cut down to an eighth-mile due to the speed of the contestants, there is some pavement in the pits from the older quarter-mile starting line. The trailer holding the Belle Dodge Coronet is pulled under a small stand of trees, and the rest of the pits are already filling up with regular competitors. That $6.00 gate fee applies to everyone. Racing for trophies? $6.00. Racing for money? $6.00. Watching today? $6.00, which is not a bad deal considering that it was $3.00 back when the track first opened up almost 40 years ago!

Unlike regular racing today, there are no dial-your-own brackets here. To run for trophies, George's son-in-law Scott Mace will classify your car based on displacement and year. Machines that dominate for more than a week or two are moved up into a class more suiting their nature. The last complaint about legality occurred years ago, since most of the trophy racers are here for fun and prefer to race those cars closest to them in performance. The one whiner who wanted a competitor ripped down paid 45.00 for the privilege, and once the protested gentleman had removed a head, George gamely stuck a yardstick down one cylinder and stated, “yep, he's legal.” That was the end of that problem for good. Unlike regular racing today, there are no dial-your-own brackets here. To run for trophies, George's son-in-law Scott Mace will classify your car based on displacement and year. Machines that dominate for more than a week or two are moved up into a class more suiting their nature. The last complaint about legality occurred years ago, since most of the trophy racers are here for fun and prefer to race those cars closest to them in performance. The one whiner who wanted a competitor ripped down paid 45.00 for the privilege, and once the protested gentleman had removed a head, George gamely stuck a yardstick down one cylinder and stated, “yep, he's legal.” That was the end of that problem for good.

If you want to run for money, there are indexed divisions based on half-second increments ranging from 8.50 to 5.50 seconds in the eighth-mile. The vintage clocks do not give reaction time; either you go red or get a green light at the start. At the finish line, the competitor running closest to the number without breaking out wins. If both cars break out, both are disqualified. No computer prints out time slips; they are hand-written at a timing booth located at the end of the eighth mile. The quickest of the divisions, the 5.50 bracket, pays 300.00 to win. At the gate, T-shirts bearing the slogan, “The Only Heads-Up Drag Strip In The World” can purchased before entering the park-like setting. If you want to run for money, there are indexed divisions based on half-second increments ranging from 8.50 to 5.50 seconds in the eighth-mile. The vintage clocks do not give reaction time; either you go red or get a green light at the start. At the finish line, the competitor running closest to the number without breaking out wins. If both cars break out, both are disqualified. No computer prints out time slips; they are hand-written at a timing booth located at the end of the eighth mile. The quickest of the divisions, the 5.50 bracket, pays 300.00 to win. At the gate, T-shirts bearing the slogan, “The Only Heads-Up Drag Strip In The World” can purchased before entering the park-like setting.

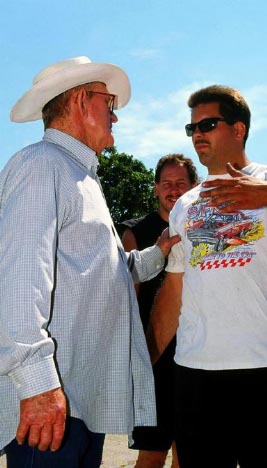

Once the big Dodge is out of the trailer, work begins for the day's two laps. Due to the converter now in the car, the plan is to make two soft passes, one using “gold dust” rosin and another as a full-length tire smoker. The racer crowd around the car is not ignorant (many of the weekly cars sport Summit decals and aftermarket equipment, and a handful are NHRA-legal Super Pro entries), but the quizzical looks on the little kids who have never seen an altered wheelbase car, an exposed supercharger, or Kohlmann's chrome-colored spaceman suit are evident. Pretty girls, seasoned citizens and partying spectators make up the balance of the attendees. The place is getting filled up, and Jolliff states today is the best weather in weeks, the stifling, 100-degree or greater heat index of the last month of Sundays having been replaced by 85 degrees and a light breeze. Kohlmann and I walk toward the tower to check out the track.

From the starting line, if you squint, the track looks a little like a cross between the Lions Drag Strip and the OK Corral. Like Lions, there is a tower and walkway spanning the width of the track, and a wooden wall goes down the left side along the starting line. The parallels quickly end there. Everything is constructed from either railroad ties, telephone poles or rough-hewn timbers. Guardrails, other then a few yards of round logs for the first 50 feet are so (which people are sitting on), are non-existent, supplemented only by a low farm fence on either side to keep people from walking out onto the surface by accident at 300 feet. A pair of steep, narrow grandstands rounds out the picture. Kohlmann wanted to recreate the past? It's definitely here, and in all of its dangerous glory.

The 31-foot wide concrete surface itself shows years of running wear, but has remained fairly level and is free from large fissures. There is no “glue” sprayed past the starting line, and traction is more of a ritual than a given. In the old days, crewmembers would bucket up water from a trackside creek, minnows and all, and throw that under the back tires; today, they bring two jugs with them. The first one, milk or antifreeze gallon in size, still contains water, which is puddled under the cars in a designated burnout area. The 31-foot wide concrete surface itself shows years of running wear, but has remained fairly level and is free from large fissures. There is no “glue” sprayed past the starting line, and traction is more of a ritual than a given. In the old days, crewmembers would bucket up water from a trackside creek, minnows and all, and throw that under the back tires; today, they bring two jugs with them. The first one, milk or antifreeze gallon in size, still contains water, which is puddled under the cars in a designated burnout area.

After physically holding the car back for a water burnout, the smaller, dishwashing soap-size bottle is used right on the starting line to squirt raw VHT onto the now-warm slicks. The car then makes a dry hop, resulting in web-like strands of traction compound hanging onto the tires, and backs up to stage. Finally, with tires squealing, the pair of racers launch (sometimes with the front tires leaving the ground) and try to keep it straight to the finish line. Helmets and seatbelts are optional, and your buddies can ride with you if you would like. The “Run At Your Own Risk” admonitions are serious. All in all, George Ray's is an unreal trip in a world now dominated by lawsuit opportunities and politically correct thinking, and great fun for every one involved... After physically holding the car back for a water burnout, the smaller, dishwashing soap-size bottle is used right on the starting line to squirt raw VHT onto the now-warm slicks. The car then makes a dry hop, resulting in web-like strands of traction compound hanging onto the tires, and backs up to stage. Finally, with tires squealing, the pair of racers launch (sometimes with the front tires leaving the ground) and try to keep it straight to the finish line. Helmets and seatbelts are optional, and your buddies can ride with you if you would like. The “Run At Your Own Risk” admonitions are serious. All in all, George Ray's is an unreal trip in a world now dominated by lawsuit opportunities and politically correct thinking, and great fun for every one involved...

We are going to make our first lap before trophy eliminations begin, and we are bringing our own ritual, the gold dust, with us. Created as dance floor compound, Southern drag racers in the early 1960s had found it would greatly enhance traction. A big part of match racing back then was brooming the gold-colored “tack” onto the racing surface and then doing multiple launches, or “burn throughs,” to melt the dust into the track and create wheel-biting traction. Brian completely fills two coffee cans equipped with homemade shaker lids with the stuff and throws a broom into the back of the truck to spread it with.

Time trials have ended and George, who addresses everyone with a smile and the words “Hey Boy!!!,” has parked his original Olds-motored roadster in the pits next to the Coronet. A small crowd gathers as Brian suits up and Keith connects the starter to the car to warm up the engine. Once lit, the wafting eye-watering smell of nitromethane fills the air courtesy of the homemade “weed-burner” headers, and the people back up, but most are grinning from ear to ear. George doesn't remember the last pro fuel car to be here, but bets from the locals seem to point to Larry Coleman's Kingfish Barracuda driven by Larry Arnold in the mid 1960s.

Since there is no crowd control, a large assembly of both racers and spectators gather around the car as it stands in the starting line sunlight a half-hour later. Brian, his spacesuit on, is walking down slowly in front of it, dumping two long 35-foot streaks of dust from the coffee cans. With the broom, he spreads it widely around to be sure the car will be in it, and then dons the face mask, gloves and helmet before climbing back inside the car. Early ZZ Top guitar riffs are blasting from a trackside pick-up.

This time, the roar of the fuel-fed Hemi sends the crowd back quickly. After a quick, hard blip to clear the engine, Kohlmann rolls into the twin dust trails and nails it. A wave of gold powder mixed with the air being moved by the back of the car rolls out behind the Coronet as it heads for half-track. People are yelling, little kids are holding their ears, and a pair of serious beer drinkers hanging on the fence are laughing like madmen. Backing up, Kohlmann does it once more, leaving hot black streaks of rubber in the gold dust, and stages up. At the green, the car launches and sashays down the pavement, the tires already beginning to boil at 100 feet despite the traction attempt, and leaving in its wake the remainder of the dust, an echo of blown horsepower and a simultaneous uproar of rebel yells and clapping. The natives like nitro just fine... This time, the roar of the fuel-fed Hemi sends the crowd back quickly. After a quick, hard blip to clear the engine, Kohlmann rolls into the twin dust trails and nails it. A wave of gold powder mixed with the air being moved by the back of the car rolls out behind the Coronet as it heads for half-track. People are yelling, little kids are holding their ears, and a pair of serious beer drinkers hanging on the fence are laughing like madmen. Backing up, Kohlmann does it once more, leaving hot black streaks of rubber in the gold dust, and stages up. At the green, the car launches and sashays down the pavement, the tires already beginning to boil at 100 feet despite the traction attempt, and leaving in its wake the remainder of the dust, an echo of blown horsepower and a simultaneous uproar of rebel yells and clapping. The natives like nitro just fine...

Like Brian, I attend to a lot of nostalgia races, and while it is nice to see old cars and hear stories from the past, the sterile conditions of today's sanctioned facilities makes it impossible to actually “recreate the past.” That was Brian's plan here, and it is working perfectly, but an added benefit is that many of the older spectators have an unbroken string of memories. Chucky Jolliff introduced us to a half-dozen characters who had been regulars at the track for almost 40 years.

“We had only been open about a month or so, and I was in the center of the track with a flag” recalls Glenn Wade, who was a starter in those early days. “During time trails, an A/Gas car and a B/Gas car were running. They both got sideways, and they came together right where I was standing. One of the tires got me and sent me flying into the air, I did a full flip and landed on my feet, not hurt but shocked. George came over and said, ‘That's it. No more of that. We'll start all of the races from the side of the track!'”

“There weren't too many big names who came out, but Joe Lunati used to race out here, and Ray Godman and the Tennessee Bo-Weevil ran here some, too,” remembers George himself. “Some of the local guys built good cars. In those days, before the Mopar 413's showed up, the big combinations was them 409 Chevys and 406 Fords. One ol' boy, he got himself a new 409 and raced it brand new the first weekend he had it. By the next Sunday, he had put some real good parts on it, and the following week, he was towing it in!”

Each individual had stories and memories of the days gone by, when the track had no trees and a creek ran down the right side of the entire length of concrete. More than one car went “swimming” in those days, and though there has never been anyone killed at the track, fires and accidents are part of the fabric of its history. Chucky himself put a few those out during his days in the starting box.

Though safety does not appear to be a dire concern, the regulars are actually careful and watch everything that is going on in the starting line's close quarters. Experience seems to keep the drivers of the faster cars from making stupid mistakes when the cars are out of shape, and the crowd moves back of its own accord when the races begin. Still, there is immense potential for disaster, and a fatal accident involving spectators would most certainly be the end of this Arkansas tradition.

On its second lap, the Belle Dodge actually hooks up without the gold dust, and Kohlmann makes his best lap of the weekend, in the mid-five second range. In Pro Nostalgia trim, the car actually ran as quick as 7.47 at 189 MPH, but Brian has since reworked to be more like Dyer's 1965 machine, and the norm is now 7.90-8.10s at an even 180 MPH. On its second lap, the Belle Dodge actually hooks up without the gold dust, and Kohlmann makes his best lap of the weekend, in the mid-five second range. In Pro Nostalgia trim, the car actually ran as quick as 7.47 at 189 MPH, but Brian has since reworked to be more like Dyer's 1965 machine, and the norm is now 7.90-8.10s at an even 180 MPH.

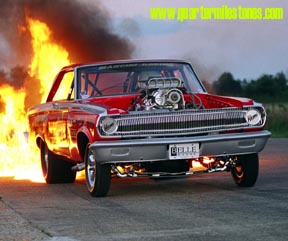

Back in the pits, the car is serviced (plugs and oil) and we wait for sunset and the end of the day's racing to finish out the weekend's activities – a fire burnout. Back in the pits, the car is serviced (plugs and oil) and we wait for sunset and the end of the day's racing to finish out the weekend's activities – a fire burnout.

Though the fire burnout had not yet been invented when Mr. Norm had retired the car in 1966, it was something that Brian felt would be a fitting end to the weekend. George agreed that we could do it down in the shutdown area, and the team mixed up a 50%-50% batch of gasoline and VHT for that purpose. This formula came from long-time photographer Jon Asher, along with the advice that smearing the rear end of the car with Vaseline would keep the gold leaf and paint intact. Though the fire burnout had not yet been invented when Mr. Norm had retired the car in 1966, it was something that Brian felt would be a fitting end to the weekend. George agreed that we could do it down in the shutdown area, and the team mixed up a 50%-50% batch of gasoline and VHT for that purpose. This formula came from long-time photographer Jon Asher, along with the advice that smearing the rear end of the car with Vaseline would keep the gold leaf and paint intact.

With the car in place, the pavement was painted in a 24-inch wide 12-foot arc of the compound with two six-foot long streaks going forward and a liquid “wick” along one edge. The idea was to start the car up far in front of the puddle, back it up so that the rear tires were placed into the streaks, light the puddle ablaze (the VHT would help slow the flame front and produce a brighter flame), and, once the fuel was burning, give Kohlmann the signal to hit the throttle and do a burnout. With the car in place, the pavement was painted in a 24-inch wide 12-foot arc of the compound with two six-foot long streaks going forward and a liquid “wick” along one edge. The idea was to start the car up far in front of the puddle, back it up so that the rear tires were placed into the streaks, light the puddle ablaze (the VHT would help slow the flame front and produce a brighter flame), and, once the fuel was burning, give Kohlmann the signal to hit the throttle and do a burnout.

After three conflagrations, witnessed only by the crew, George and a few spectators who had stayed around, we completed that effort and began the job of getting ready for all night rides; back to Wisconsin for the team, and to eastern Tennessee for me.

Brain and Keith had to pull the borrowed converter back out the car, which Chucky had promised to hand-deliver back to Junior Ferrel in Cape Girardeau, Mo., over 100 miles away, later in the week. By 9:30 PM, my rental car was quickly winding its way back up Route 412 toward the Missouri border. Brain and Keith had to pull the borrowed converter back out the car, which Chucky had promised to hand-deliver back to Junior Ferrel in Cape Girardeau, Mo., over 100 miles away, later in the week. By 9:30 PM, my rental car was quickly winding its way back up Route 412 toward the Missouri border.

The glory times of match racing have long since disappeared, superceded by the high cost of professional racing and a loss of the excitement and personalities that had made the heady days of early funny car so attractive. Kohlmann's hybrid Mopar and George Ray's Wild Cat Hot Rod Drag Strip belong to each other. Neither regards the radical changes to the sport with much respect, preferring instead to enjoy a simpler and decidedly more dangerous era.

The fact that we worked on the car in the pits at Sikeston Drag Strip until 1:30 in the morning wasn't lost on anyone in the team; such problems were part of the daily struggle in the early days of exhibition racing. So were all-night drives across multiple state lines, a steady intake of caffeine and nicotine, forgetting to eat, and racing at backwoods places that, well, just couldn't exist unless you saw them yourself. No one can predict how long the 40-year-old strip of concrete just inside the Paragould, Ark. city limits will last; how soon before it too will join its compatriot properties in Orange County, Calif., Yellow River, Ga., York, Pa., or Center Moriches, Long Island, New York, as footnotes in drag racing history. For one perfect July afternoon, however, all in the world was right, and nitro exhibition racing was the center of attention to a whole new group of fans. Who says you can't go back again? The fact that we worked on the car in the pits at Sikeston Drag Strip until 1:30 in the morning wasn't lost on anyone in the team; such problems were part of the daily struggle in the early days of exhibition racing. So were all-night drives across multiple state lines, a steady intake of caffeine and nicotine, forgetting to eat, and racing at backwoods places that, well, just couldn't exist unless you saw them yourself. No one can predict how long the 40-year-old strip of concrete just inside the Paragould, Ark. city limits will last; how soon before it too will join its compatriot properties in Orange County, Calif., Yellow River, Ga., York, Pa., or Center Moriches, Long Island, New York, as footnotes in drag racing history. For one perfect July afternoon, however, all in the world was right, and nitro exhibition racing was the center of attention to a whole new group of fans. Who says you can't go back again?

George Ray's Dragstrip, 485 Highway 135 S., Paragould, AR 72450

Phone number is 870-236-8247

“NITRO HALLUCINATION”

PRODUCTS CURRENTLY FOR SALE

TITLE: Driver Brian Kohlmann does a fire burnout in the nitro-burning Belle Dodge S/FX 1965 Dodge Coronet. This 426 Hemi beast is a tribute to Mr. Norm's similar machine of the 1965 season. Scenes from Nitro Hallucination article in Hot Rod magazine, showing action at George Ray's outlaw backyard dragstrip in Paragould, Arkansas.

| ITEM |

DESCRIPTION |

PRICE |

PURCHASE |

| GR1 |

8x10 Fire Burnout |

$14.99 |

Buy

Now! |

| GR2 |

16x20 (hand printed by Don Gillespie - very limited quantities) |

$39.95 |

Buy

Now! |

| GR3 |

20 4x6

prints of George Ray's Wild Cat Outlaw Drag Strip |

$89.95 |

Buy

Now! |

| GR4 |

7 Shot

FIRE BURNOUT SEQUENCE – 4x6 |

$29.95 |

Buy

Now! |

|

|